Like many, I fear that I will have said something insensitive or incorrect here, or that I’m taking up too much space. I apologize if that is the case. But more than that, I fear how I will feel down the line if these words never left my mind. TL;DR: go listen to Dave Chappelle.

Fear I. Death

Death is unrelatable. We die once, and nobody tells us what it’s like to die. We can grieve, but most of us can’t empathize with the dead, or even the dying.

Fear - fear of our own death, and the deaths of our loved ones - on the other hand, is much more relatable. Most people, I’d think, are scared of certain aspects of death. If you’ve made it to now, you’ve probably feared for your own life at some point, and probably irrationally so (unless you’ve had a serious medical condition or were in an accident). Maybe you can’t relate with the black men who died at the hands of police officers, and maybe you think the world is not so simple, or maybe you simply cannot imagine the police to be anything other than defenders of justice. So let’s put all the nuances and the politics aside for a moment and look at the first principles - I promise, we’ll revisit them.

Don’t try to relate with George Floyd’s death. Relate with his fear. For more than 8 minutes, he went through the fear of an imagined, then imminent, death. His own death. I have this recurring and entirely irrational fear of (for some unknown reason) being bagged by the mafia, tied to cement blocks, and tossed into the ocean. I’m not that scared of being dead, strangely enough. I’m scared of the 90 seconds of hopeless struggle I will inevitably put myself through just to realize over and over again that I am going to die, and that there’s nothing I or anyone can do about it. I don’t know what particular thing calls up that fear for you, maybe it’s being buried alive, maybe it’s getting a terminal disease, maybe it’s having your car flipped over on a remote highway and slowly bleeding to death. Whatever that is, close your eyes and call it up into your imagination and live it over and over again, for a minute, two minutes, five minutes. Imagine all the things you wish you could have said or unsaid to the people in your lives, then realize that it is, in fact, too late.

That’s the fear of hoping against the inevitable. It’s pretty unpleasant, right?

Fortunately, for most of us, that fear dissipates the moment we open our eyes. But that is not the case for some of us. That fear, for 8 minutes, was George Floyd’s fear. It was Eric Garner’s fear. That IS the fear of black men young and old and it’s a goddamn travesty in this fucking country that those fears are actualized, day in and day out, and caught on camera, with nary a consequence.

More concrete is the fear of the death of a loved one, whether imagined or sometimes, unfortunately, unavoidable. These people - someone’s loved one at your age, your brother’s age, or your father or your son’s age - are going to potentially find themselves fighting for their lives after being accused of using a fake $20 bill, selling loose cigarettes, or, you know, dancing to the music while going to the shop to get ice tea. In turn, their parents, their siblings, and their friends and coworkers have to face the fear that their loved ones might never make it home on an otherwise perfectly unremarkable day, every single day. Feel this for a moment: you get a call from an unknown number informing you of your worst nightmare, not because your boy did a dumb boy thing that you’ve told him millions of times not to do, like backflipping into a pool landing head first, but because the police, well, killed him in broad daylight. The color of his skin is not the official cause of his death, but we know that it might have saved him had it been a different one. We know that.

And so the first principle is this: not a single person, nor their families, should be subjected to the realization of these otherwise absurd fears for simply living their lives, the lives you and I live day in and day out, the lives that we now witness abruptly ending on what feels like a weekly basis. This is an axiom of life and a fundamental human right in a so-called “first world” country. We can discuss solutions and trade-offs, and we should, but if this is not a principle you are ready to defend at all cost, for your own life and for the lives of people who share a world with you, then there’s no point reading further.

Fear II. Power

I don’t think all cops are bad. Like all professions, most people in it, by definition, are average, and there are those that are really good at their job, and there are those that are really bad. But being a police officer, like being a healthcare professional or any other emergency personnel, is not a regular job. There is an inherent asymmetry when it comes to life because time is asymmetric: there are many opportunities to save and prolong a life, and every successful attempt buys you a new opportunity, but there is only one opportunity to end a life if you so choose to take it, either by accident or with malice.

As a result, while the person whose life you’ve saved may be eternally grateful, you’ve only extended the natural course of things, and because it is your job, you did what you were supposed to do. The only reward comes from knowing how many lives you’ve touched, and if you did it for long enough, maybe a medal. Coupled with the fact that, in a stable society (though that’s looking less and less applicable to America), people rarely come across dramatic life-or-death situations that require forceful intervention, suddenly the taking of lives becomes a lot more obvious - and easy - than their prolongation. I think this is important to keep in mind.

I’m biased, though. I’d grown up entertaining the notion of becoming a police detective, because I loved Sherlock Holmes and Detective Conan. Even though Sherlock Holmes was actively antagonistic towards the police constables, short of opening my own private agency, becoming a police officer seemed like the only real option for solving mysteries for the good of the people. Even if you took away the magnifying glass and cool CIS gear, at the core of its idea, the police is a gentle but just force: it’s who you call to get a kitten off of a tree (I didn’t watch a lot of shows about firefighters) and to shoot a villain dead. I never considered it seriously, though, partly because my mom would kill me first, but mostly because I thought I didn’t have the nerves for it: sometimes, I (still) scream like a little girl. If you gave me a loaded gun, I honestly don’t know if I’d make the right call time after time, when it comes down to a perceived threat to my own life vs. giving someone a chance to change theirs. Such is the burden someone carries in a profession universally hailed as heroic: to routinely put your own being at risk in order to serve, help, and save others, even if you have the power of the law backing your gun.

After we moved to Canada, I spent my teenage years listening to Tupac and Jay-Z talk about crooked cops, and through my involvement with various organizations, and my own (very minor) run-ins with the law, it dawned on me that 1) any individual police officer does not always try to do good, and 2) the law affects me - a scrawny Asian teenager - a lot more differently than it does people who appeared to be different, even though I did my very best to wear as many oversized and hooded clothing items as I could, because that’s the culture I grew up in and wanted so desperately to be a part of. These last 6 years in the U.S., though, marshaled a whole new level of degeneration in my idea of what the police represents. Eric Garner’s murder made an impression on me, and that moment shifted my perception of what reality in the vaunted United States of America - especially for poor and black people - really looks like, and it’s only getting worse. I had wanted to write something then, and I’d wanted to write something after every murder: Alfred Olango, Philando Castile, the list goes on and on and I’m ashamed that I don’t even remember all the names anymore. I could never find the right words, because it was senseless - it literally didn’t make sense - but somehow it always seemed like a complex situation. No matter, these are the words I could muster up today.

Derek Chauvin, the man who killed George Floyd, is without question a murderer, and his colleagues accomplices. This is as plain as the day from which we see the video recording: he was not acting in self-defense, it was not an execution ordered by the law, and it was certainly not an accident, as those 8 minutes slowly unraveled and the dying man called out for his dead mother. If you change his uniform for any other colored shirt, you will easily see the situation for what it was: murder. However, the uniform and the badge are precisely the things that complicate, not the reality of the situation, but how people can choose to see it. I get it. People want to side with the law and believe that the police officers did nothing wrong because they must have had a reason to do what they did. They must have, right? These petty criminal men, even if they didn’t deserve death, should not have resisted arrest, right (even though we see again and again that cooperation does not mean survival)? Maybe this benefit of the doubt rightfully applies to most police officers, in most situations, but make no mistake, it does not apply here. Because of the uniform and badge, Derek Chauvin was not forcefully stopped nor lawfully apprehended on scene for killing another man. Because of the uniform and badge, Daniel Pantaleo, the officer who choked Eric Garner to death in 2014, was apparently fired in 2019, 5 years later, with no criminal indictment. Such is the power granted by the uniform and badge.

Like I said, I don’t believe that all or even most police officers are “bad”, whatever that means, and I certainly don’t have the expertise in police reforms or community protection policies to offer concrete and informed thoughts. Some of the conversations that have recently come to the forefront of our attention about defunding major metropolitan policy forces, which can take up a significant proportion of the city’s funding and upwards of billions of dollars, seem hopeful and innovative. So are the conversations about police reform, investing in developing local communities, healthcare, and education, and god forbid, de-weaponizing your local traffic cop. Fuck if I know what the best thing to do is, and my ignorance on these topics is not to imply that these conversations have not been happening for a long time, but simply to say that I write from how I feel, and how I feel is this: the uniform and badge were granted by the people to defenders of justice so that they can wear it with pride when they repeatedly put their lives at risk, when it becomes all but necessary to use deadly force to diffuse a situation (which, coincidentally, happens a lot more often in America. I wonder why). Drawing your gun at the first available opportunity is not that, choking an unarmed and defenseless man is not that. You have turned your proud shield into an ugly and small mask, behind which you wield your powers while hiding your fear of all that threatens, not your personal safety, but your ego and your perceived way of life - an asymmetric and unfounded fear that gives little back while taking the whole entire lives of others.

Post-script: there is so much more to say about larger structural and systematic issues within American law enforcement, i.e., how police forces are trained and militarized that turn good-doing people into…less good ones. Again, I’m obviously not an expert, and tons of conversations I don’t know much about are happening, but here are some police stats and a personal statement from a former cop - it’s a good read, even if anecdotal (thanks, J). A quote:

The question is this: did I need a gun and sweeping police powers to help the average person on the average night? The answer is no. When I was doing my best work as a cop, I was doing mediocre work as a therapist or a social worker. My good deeds were listening to people failed by the system and trying to unite them with any crumbs of resources the structure was currently denying them.

Fear III. White Supremacy and the “Normal” Way of Life

Boy, that escalated quickly.

People continue to confuse their wish of a meritocratic society for the delusion that that is the world we live in today. Often, we wish for something so badly that we believe it to be true. That’s why “black lives matter” is a poor slogan. It is a statement of a platonic ideal, not a statement of reality. Really, what we want to say is “black lives should matter, but they don’t, so please, let’s do something about it, because we want black lives to matter.” To the people that suffer from the reality that black lives don’t matter, it doesn’t make a difference, because no black man is going to confuse the platonic ideal and the reality today when their life can end because they got pulled over for a minor traffic non-offense. But for a person who doesn’t know the difference, and who thinks the world they live in is a just and fair world, either by blissful or willful ignorance, “black lives matter” sounds like a chant for exceptionalism (i.e., “black lives better”…how do people come up with this shit). Unfortunately, the exceptionalism is not in what we want for black lives, but in how it currently is, and not in a good way.

On the other hand, “all lives matter” is a curious response. I don’t disagree at all, all lives do matter, of which black lives are a subset. Saying “all lives matter” in response to “black lives matter” contributes literally no semantic information to the conversation when taken as statements - it’s all true, we agree. But that ignores the context of this conversation, and if I’ve learned anything during my PhD, it’s that context matters tremendously in language and communication. So what is it really saying?

Here’s my analysis: I suggest that we treat “all lives matter” from the same perspective, not as a statement of a platonic ideal, but a request, and in this case, a counter-request: “other lives should matter too” and “my life should matter too”. In most cases, this means “white lives matter too”, though my fellow Asians are not exempt from this (which always boggles my mind, more on this later). More specifically, the word “life” has a different meaning here: all lives are not literally at risk the same way black lives are, but people fear that these protests and reforms and affirmative action policies will threaten, not their physical lives, but their way of life - a life of normal. People fear that all this pot-stirring means that a spot at Harvard will be given to an undeserving colored life, rather than a hardworking and law-abiding, and most importantly, uncolored life, a life that has done all that they can to follow the rules of this just and meritocratic society, because that’s the way it should be.

Except, that’s never been the way it is.

One unforeseen but much appreciated consequence of our reaction to yet another senseless police-killing of a black man is that it has pushed every profession to do some introspection on its biases towards black and other-colored people. And hopefully, also minorities of different kinds, be it gender, race, sexual orientation, or disabilities, and to appreciate their unique contributions. Some of that, no doubt, is lip service. But as a friend wisely (and sadly) put it, at this point, even lip service and pretend-wokeness is better than staying silent and complicit, because at least it keeps the fire going. What has come up over and over again during this process is that, well, black and colored lives and their contributions don’t matter…even at the fucking Bon Appetite Test Kitchen?? Goddamn it, my one source of warm reprieve.

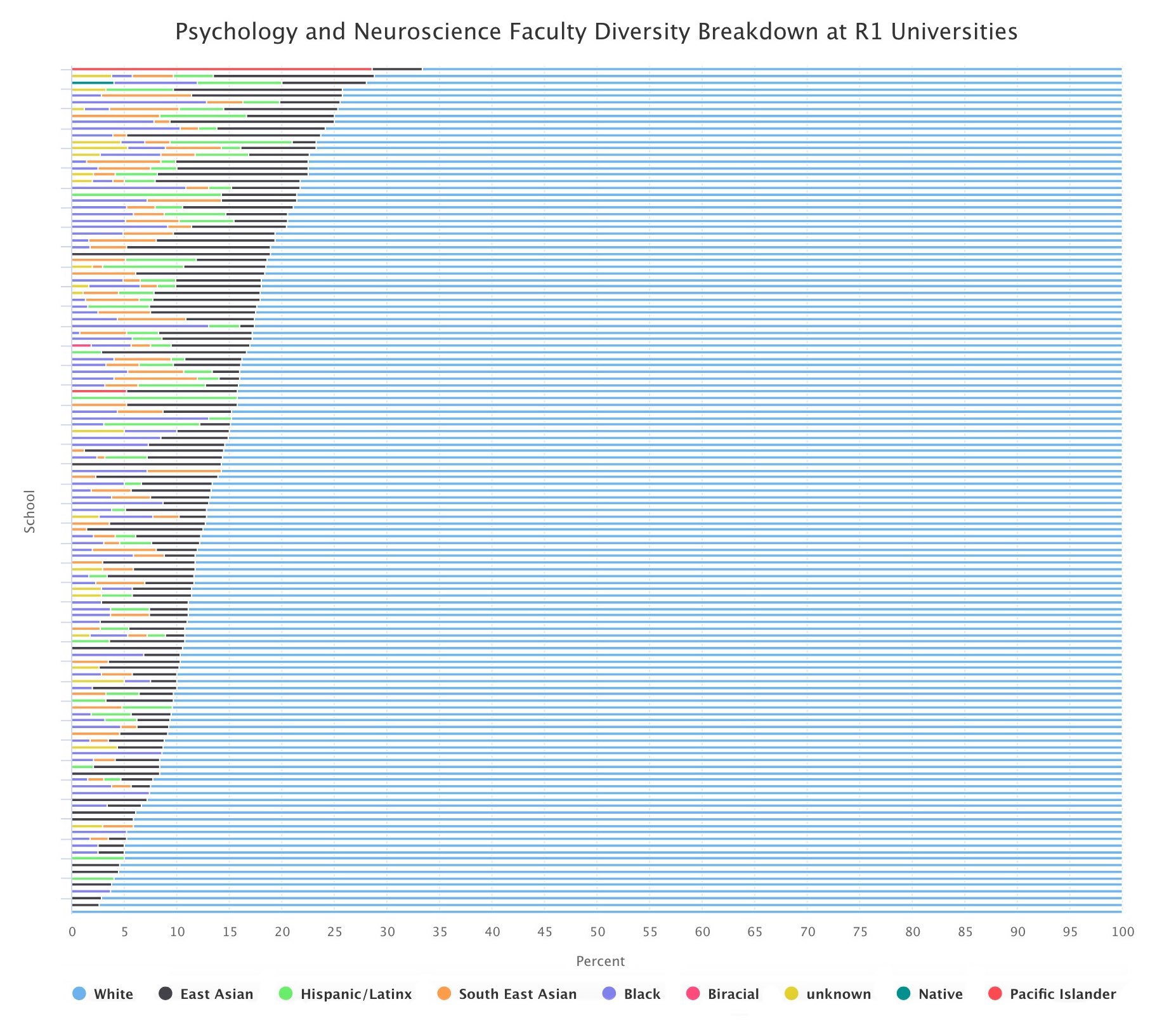

Academia, though, is especially and unsurprisingly egregious. Someone fact-check this source, but there was a tweet going around (from unpublished but formal research) showing the proportion of faculties at various R1 university psychology and neuroscience departments, and one of them literally had 0.

Zero.

What’s more surprising is the consistent denial that this is a fact and a problem from people of all categories within academia. If you grew up a white straight man, possibly even upper middle-class, to become an academic - sure, I can see where that perception comes from, and I don’t blame or even dislike you: as far as you’ve seen, the world is fair and meritocratic, and if I were you, I’d want to keep it the same way too. As I alluded to above, however, what’s hilarious and perplexing to me is how there are any people of literally any other labels, and their intersections and inter-intersection, can maintain that this whole enterprise is “fair” and working for them, because every single one of them, of us, is getting fucked. The answer is not yes or no, the answer is “by how much?” Women? Check. Gay? Double check. Poor? Check, unless….you’re not Matt Damon and/or a white janitorial staff that can do math, are you? Black? Fam, CHECK. Gay, black, and poor? I’m sorry sir, are you lost? This is not a Wendy’s.

Obviously biases are not specific to academia. If anything, academia is perhaps progressive enough - compared to law, finance, and medicine - to openly acknowledge these problems. But I do find it curious that academia has not solved these problems together, working from the foundation that all perspectives are valuable, from purely a perspective of bringing in cultural insight. My hypothesis is that scientists, more than any other professions, dedicate their lives to finding order in this world with limited available data - finding order often prioritized over getting more data. In this case, it appeals to our inner peace to believe that there is order and justice in this ascetic profession, where we are devoted to nothing but the truth. And when we want to see it, we do, because then we can focus on science, not politics. Politics is uncomfortable, messy, and frivolous, not for your pure analytical scientist-type to touch (or maybe I’m projecting). But just because we do not see how a compounding of systematic frictions work in minute and invisible ways against our colleagues, and often even against ourselves, it does not mean it is not happening. Everywhere there is people, there is politics. My parents moved from China to Canada because they thought North America would have less covert and insidious politics for me to deal with, and I thank them for sacrificing their lives back home to do it. But they were only partly right: there is covert and insidious politics everywhere, America included, it’s just that minorities usually don’t even have the privilege of participating in it, because you can be spotted as an outsider from miles away - black, yellow, or brown - even before your funny mannerisms and your funny accent and your funny-smelling lunch had a chance to give you away.

Or maybe old white dudes just don’t get it because they didn’t have to deal with all this racial diversity non-sense back in the old days. Equally plausible.

I might sound bitter, or that I feel venom towards certain people, or even that I’m pushing aside the voices of the rarely-represented colored scientists to air my own grievances. Those are not my intentions, nor am I bitter. I simply write what I believe to be truth, truth that I have accepted with no harsh feelings. Being a straight Asian man in academia, by all accounts, is as natural of a home as I will ever find (though that comes with its own problems). But growing up in this society as a minority, you must first acknowledge the truth that you are different from normal, and you must certainly not expect to walk into someone else’s home and be accepted and crowned king right away, or ever. That is delusional. These are the things I will tell my children, and my grandchildren, and I will be grateful of my privilege that I do not have to fear for my life or the life of my family, nor will I fall victim to the fears of a police officer or vigilante gunman as I take my long evening walks into nice neighborhoods. I do not have to tell my kids to put their hands where officers can see them when they are pulled over, or to make no sudden movements under any circumstances, ever, in the presence of law enforcement. Actually, no, that is not a privilege, but a right, and a right some of us do not currently possess.

As for the changing way of life: I, too, fear sometimes that what could have been mine is given to someone else on the basis of my and their color, gender, or whatever attribute the institution wants to put on a poster on a given day. That is a natural fear, and if you fear the same, you shouldn’t feel shame or run from it. It is a competitive environment, and we all want the best for ourselves. If I had inner club privileges, I’m not sure I’d be so quick to give that up either. That’s why I don’t feel any animosity towards any individual that makes up and unknowingly participate in this institution, white or not, because they were born into it. Many of my best friends are white (…and that sentence will never not sound stupid, even if true). But if you are a sliver of the minority pie - not only in race and color, but in every other attribute - that’s not empowered by this system, then you will empathize with the struggles of your friends and colleagues, not in degree, but in kind. You will know what it’s like to be in a place where you’re not expected to be. And if you can let those fears pass through you - after all, they are rarely a matter of life and death - you will see that this whole place is full of people that’s not suppose to be here - people that differ, are not normal - and that we can unite in our differences, and in our fears, to make it a better place for everybody.

Post-script 2: that ending got a little dramatic there, but it felt right. Sue me. I guess what I really want to say is: for as long as I’m in this thing, I offer my help and potentially poor advice to anyone - no matter what color or shape, but especially those underprivileged - wishing to pursue their goals in brain and cognitive sciences, freely.