This is the second of a series of posts where I talk about the current state of science, and today’s in particular will begin by looking at the reproducibility crisis, and how a seemingly technical problem can give rise to this real-world issue.

I was sitting in lecture for the class that I’m TAing this quarter last night

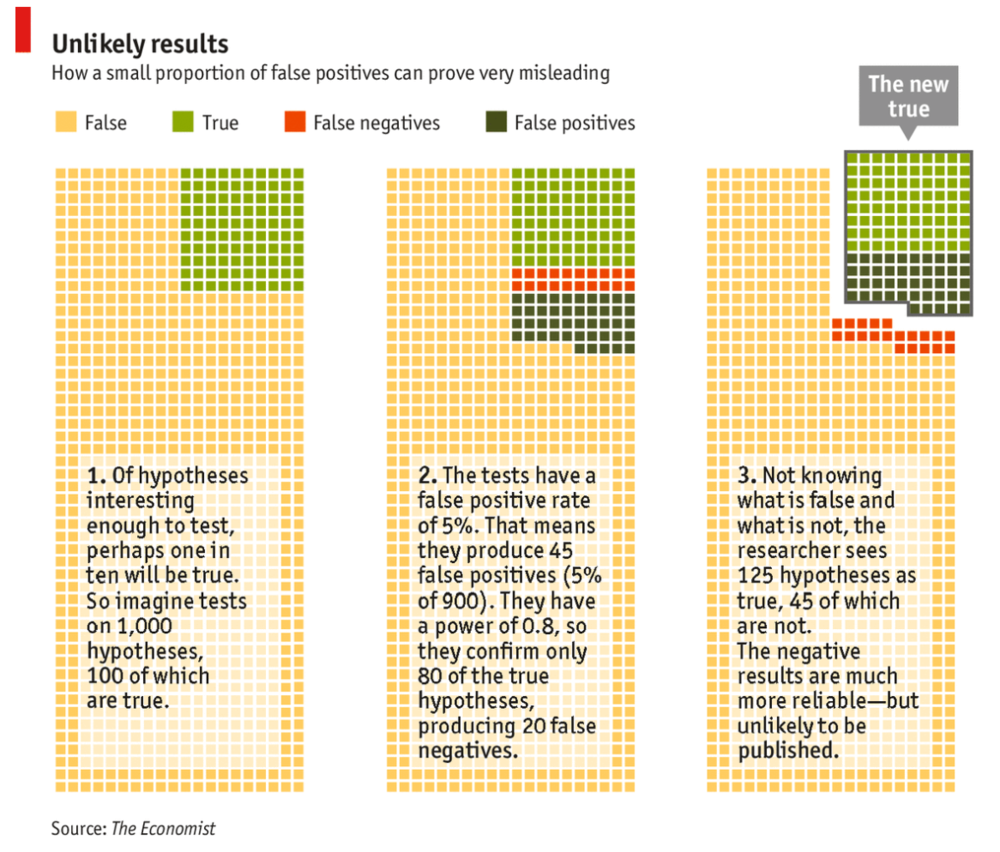

- introduction to data science - and we began to talk about the current reproducibility crisis in science. The fact that reproducibility has been an issue, especially in biological and psychological sciences, is not news to me. In the last couple of years, there have been various accounts of this particular problem in the media, as well as scrutiny from the scientific community (see here, and an analytical explanation for neuroscience specifically here). What caught my eye, though, was the graphic below, taken from the accompanying article from the Economist:

False Positive Results by Chance

Briefly, this schematic aims to explain why there seems to be so many false

positive (hence irreproducible) findings in science. They begin with the

assumption that most scientific hypotheses are false, and only a small

fraction (10% here) of them will turn out to be correct after data is gathered

through experiments (panel 1). This seems consistent with intuition, since

most of our ideas will turn out to be crap, and a lot of experiments simply

don’t work out. This is now purely personal speculation, but there seemed to

be a kind of a golden-age of science - at least in biology - where fundamental

and groundbreaking results were discovered in a flurry in the 80s and 90s.

Nowadays, it seems harder to find the golden needle in a stack of hay, hence

most of our hypotheses - the ones that we were so convinced would work after 3

beers with the lab - are probably wrong.

Panel 2: even with careful statistical analysis, an experiment has the possibility of returning a false positive or false negative result. For example, if we hypothesize that eating strawberries makes your brain larger, we will set out to gather data and test this relationship. We often use a p=0.05 threshold for significance, meaning that if there was indeed no real relationship between strawberries and brain size, then only 5% of the time will our experimental data - given the threshold we set - produce an effect large enough BY CHANCE that we then go on to interpret as true. It follows, then, that 5% of all false hypotheses will return positive results by chance, not out of misconduct (45 out of 900). Similarly, a portion of actually positive findings (true hypotheses) will be deemed false after our experiments, also by chance (20% of 100 = 20). So in the end, we end up with 80 (true positive) + 45 (false positive) = 125 positive findings.

Panel 3: of course, overwhelmingly, it is positive findings that actually make it out of the lab, so that we can make another headline that reads “Scientists discover _____”. Now, if we go back and re-examine these 125 discoveries, it’s likely that we will not be able to reproduce the majority of those 45 false positives (hard to get lucky twice). Hence, it seems that science is in a dire reproducibility crisis, since around a third of the positive findings cannot be reproduced by independent labs. There are real and systematic problems that make this happen. For example, bad incentive structures where a scientist is judged only by publications and citation counts will want to publish as much as possible to get grant funding and tenure so they can keep doing the science they love. In very few instances are these actually due to misconduct and conscious malpractice, and the scientific process was designed to catch these kinds of errors anyway. However, over time, sloppy standards get sloppier at no fault of any individual, and no one would bother to try to reproduce a work because reproducing someone else’s exciting finding won’t get you nearly as much recognition, so why not invest these precious grant dollars more efficiently? These are problems that most scientists acknowledge and lament, and wish to be different (I believe), so I won’t belabor the point here, though I may write a separate post about these larger issues.

How Theory Can Save Us

What I want to focus on is a new insight I stumbled upon while looking at this

illustration: people can’t publish null findings. This fact is old as time

itself, and even has its own name: publication bias. It describes the

situation where the result of an experiment influences whether it will get

published, and most of the time it’s towards a positive bias. In other words,

only “discoveries” tend to get published. I was exposed to and made wary of

this the day I started graduate school, because neuroscience as a field seems

to be one of the worst offenders of this. Almost every single person in the

scientific community laments this, though efforts have definitely been made to

curb this practice via mechanisms like pre-registration, where one shares the

plan of an experiment prior to actually conducting it, clearly stating the

hypothesis and expected finding. Publication bias is so pervasive that I never

really stopped to think about why null findings are unsexy and unpublishable,

until I saw that second panel in the schematic, and realized just how many

more null findings there probably are compared to positive findings, and how

much value these results would add to our body of knowledge about the brain at

large.

But why aren’t these null findings published? Essentially, it boils down to one thing: null findings are unsexy because it doesn’t tell you anything informative. But failure to find anything is not uninformative on its own - it is only so because there is no theory behind why it should have NOT failed. Put it another way: if we think of most neuroscience experiments as fishing expeditions (biology is stamp-collecting, after all), going out into a random patch of sea and casting your net and not getting a single fish is not that surprising, therefore not very informative. However, if you are in the same patch of sea, lowered an empty bucket, and proceeded to not raise any water, this would be pretty informative, and certainly publishable. Why? Because our theory about the sea, water, and physics tells us that we really should expect to get water, and thus not getting water with a bucket means either: a) your bucket is leaking, b) physics is broken. Think about it: if in a well- conducted and well-controlled physics experiment that you found that an object did not drop to the ground after release, you wouldn’t just say, “oh well, just another failed experiment, back to the lab tomorrow.” No, you would probably publish a Nature paper saying you found a spot on Earth where there is no gravity. Expectations built from theory, or the lack thereof, is precisely what makes null findings informative or uninformative. If we have some expectations for how a neuroscience experiment would go - I’m not just talking about a hypothesis, I’m talking about the quantitative and falsifiable explanation we have in our heads FOR that hypothesis - then a positive and a negative finding would be equally informative. In fact, a negative finding is probably MORE informative, because it means your theory needs to be revised, which forms the basis of falsifiable science. But if we have no theory? A null finding is just another empty trip out to sea.

How will this help with the reproducibility crisis? Well, I think if we started to build actual neuroscientific theories that we believe in and can work with in a quantitative way, we will slowly be rid of the publication bias. After all, the most valuable artifact of physics is not the collection of empirical observations that we gathered in the last 200 years, it is the set of generalizable and useful theories we were able to abstract from and refine with the help of those observations. Similarly, a coherent theoretical framework in neuroscience and biology will shift the focus away from stamp- collecting and towards knowledge-building. Once the community at large accepts and values works that falsify theories or reproduce existing evidence, then we can move towards a sustainable incentive structure.