Every two weeks or so, I am faced with the innocent but extremely daunting question of “so, what do you study?” This almost always happens in an Uber/Lyft ride, and I now have a routine that I go through before carrying forward with this conversation. The routine consists of thinking for half a second whether I really want to tell this person that I study Cognitive Science, and then inevitably deciding to tell them that I study neuroscience. 9 out of 10 times, bless their hearts, they will respond with: “so you’re going to be a neurosurgeon?” And I will proceed to tell them, no, you have to be a real doctor to do that.

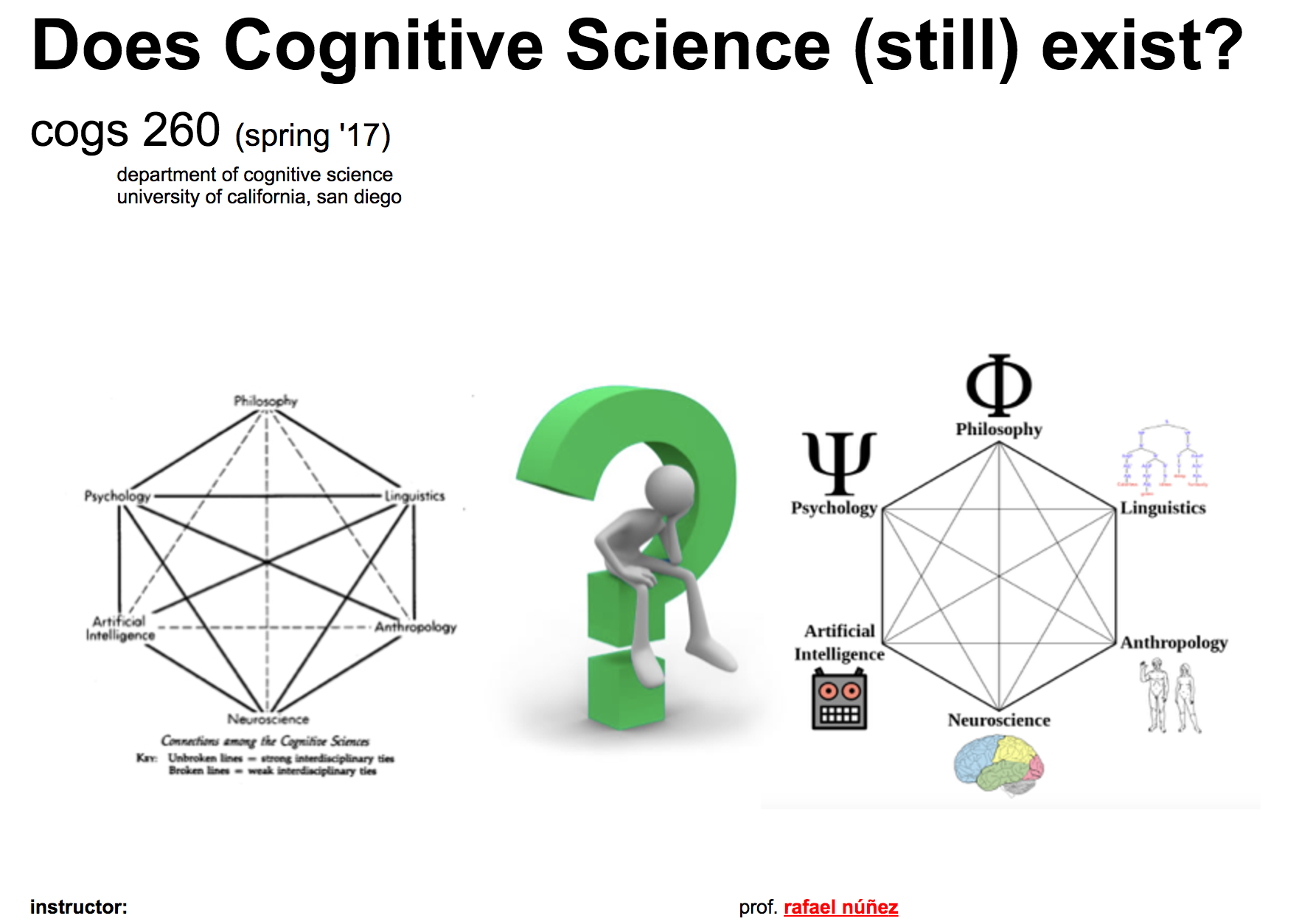

But why do I tell my Uber drivers that I study neuroscience? Well, in part, because it’s true. My day to day activities involve almost solely of trying to understand the structure and dynamics of the biological brain. But on the other hand, I tell them that because if they were to ask what cognitive science is, I would have no clue what to tell them. This is not because I’m a terrible student. Consider this: one of the most asked question within cognitive science, in my 3 years of experience being in graduate school, is “what is cognitive science?” We were asked this question during our first day of class, and we still ask ourselves this question on a weekly basis. Still not convinced? The image above is from the website of a course a professor is putting together for the new quarter, that I literally just got an email for. I don’t know if other fields of research are similarly introspective, but I also don’t know any other field that is as interdisciplinary as cognitive science. Whether cognitive science, as it exists today, is interdisciplinary or cross-disciplinary is up for debate, but the fact is that you often have a room of professional academics that research wildly different things. This is particularly true in the CogSci department at UCSD, but a look at last year’s proceedings from the Annual Meeting of Cognitive Science Society - an international gathering - reveals similar sentiments: lacking a better word to describe it, the collection of these papers seems pretty random. This rich multidisciplinarity, though, is not the cause for the lack of identity, but another consequence.

A mind split

Digging a bit deeper, you will recover a theme in that collection. Cognitive

science, to be sure, had its glorious days. About 30 years ago, CogSci gave

birth to some truly avant-garde work in psychology, neuroscience, and as many

will know, artificial intelligence, specifically in the form of artificial

neural networks. In a way, CogSci was just as blended as it is now, but for

whatever reason, in the 30 years that span the creation of the department at

UCSD and today, it has lost any semblance of a coherent identity. The reason

for that, I believe, is the discretization of the different aspects of the

“mind”, or cognition. Ultimately, if you ask a cognitive science to give a

single and definitive answer as to what cognitive scientists study, it would

probably center around the study of the mind, within their specialized

context, like learning, social interaction, or spatial navigation. Some might

say it’s the study of “intelligent systems”, but pushed hard enough,

intelligence is ultimately measured in a mind-like way. You probably wouldn’t

get this answer unless you put a gun to their heads, though, because “mind” is

a fluid concept that is intuitive but very hard to define scientifically.

Anyway, 30 years ago, a hodgepodge of smart people getting together to study the mind works because the specific details haven’t been mapped out yet. Our understanding of the brain, as well as other intelligent systems, was poor, and creating a computer program that mimics some aspect of human behavior meant you were getting somewhere in figuring out the mind. It was the corollary to the idiom: what I cannot create, I do not understand - what we can create together, we might understand. Fast forward to 30 years later, I think our understanding of the different - physical - components of the “mind” is too detailed for abstract conversations across different perspectives of looking at the mind. At the same time, it is not yet detailed enough, largely speaking, to support an actual rigorous scientific discussion linking one field to another. Neurons in the brain are not the same as neurons in a deep network, they just aren’t. This exposes a fundamental problem in the way we have been looking at cognition, and it’s that “cognition”, in its essence, is a functional metaphor that we have been using interchangeably to describe different natural phenomena, which is losing steam in the face of better and more faithful metaphors - scientific models - of these different systems.

Cognition as a metaphor

One of the most fascinating things I’ve learned in my 3 years here is how

completely different physical systems can exhibit similar intelligent

behavior. For example, slime

mold is a kind of amoeba-like

organism that, as a group, can solve some very difficult geometrical problems.

On a bigger scale, cells in our own bodies organize together to form very

intricate systems, like the brain, that enable us humans to become pretty

smart. And at the biggest scale, societies are made up of millions of

individual persons that also, somehow, give rise to behaviors that are way

more complex than the linear combination of their constituents, phenomena like

cultural norms and macroeconomics. In a particular department of cognitive

science, you might find professors that study each of those things, and

rightfully so, because they all study some mind-like, intelligent phenomenon

that ultimately seems orderly but is difficult to characterize. Even more

incredibly, the mathematics and other tools they each use can be identical,

tools like dynamical systems, graph and network theory, etc. However - and I’m

sure I will look back on this in 3 years or so and feel stupid - I think there

are a few pressing issues we need to address before acting as if everybody has

a common goal.

Currently, my personal opinion is that cognition is a functional metaphor that we, humans, have imposed on natural systems all around us, kind of like an anthropomorphization of purely physical things. At the core of it, it’s rooted in our own consciousness and belief that we have an intelligent mind, and our current understanding of the human brain fuels the belief that the brain functionally gives rise to the mind - which is a functional account of the brain. Of course, that’s not strictly false, because taking away the brain will obviously also take away our ability to perform certain behaviors, like seeing, reaching, and scrolling through Facebook. But at the same time, it’s a metaphor in the sense that the physical behavior we are able to produce is a natural, physical consequence of something the brain is doing, not a functional consequence. I find this concept to be most easily distinguished via perception and action, and most confused when thinking about “thinking”. For example, muscles in your arm are innervated by neurons in your spinal cord, which are in turn connected to motor neurons that reach down from your brain. It is therefore not very difficult to think of the whole chain as a purely physical system: neurons in the brain fire, arm moves. Not that the problem of how your brain makes that happen in such a precise way is not extremely difficult, the point is that we can think about this whole sequence of events just by tracing the ions that pass through layers and layers of cell membranes, bypassing any need for “cognition”. The problem arises, though, when we want to talk about WHY you decided to move your arm in such a way. There, we are stuck with an extra layer of metaphor: the brain gave rise to the computation required to initiate this volitional movement. And if we’re not careful, we would conclude that that’s the brain’s function! This seems both extremely intuitive but also extremely absurd. After all, we would never say the function of electrons is to pass charges from the battery to your phone screen! No, we simply describe electrons for what they are in the entangled physical system that is your phone.

What is the right metaphor, then?

To be sure, an “electron” is also a metaphor. It’s a scientific model of a

phenomenon that is able to consistently describe, and more importantly,

predict, things that have happened in the past and things that will happen in

the future. These metaphors are updated constantly when we discover new facts

about the world through scientific experiments. In that sense, neuroscience

(cognitive neuroscience aside) is an attempt to describe the brain with these

kinds of purely physical metaphors: ions, membranes, circuits. We can, and I

think we should, attempt to describe the nervous system as completely as

possible at this purely physical level, through metaphors that describe its

structure and dynamics. This doesn’t mean we should not care about behavior.

In fact, we can easily combine this physical system with those for which we

already have working, descriptive metaphors. Really, we’ve been doing this for

organs in our body for a long time, by studying their anatomy and dynamics,

like the lungs and the heart. But for whatever reason, we feel that there is

more to the brain. Again, personal opinion, but I would say this is probably

the disastrous result of the rushed marriage between psychology and neurology:

we’ve always wanted to understand ourselves more, from a philosophical

perspective, through the study of psychology, and we accidentally stumbled

upon the fact that people missing parts of their brain also have psychological

abnormalities, so why not put two and two together, nevermind the possibly

uncrossable chasm between these two metaphors?

So what good is the metaphor of the mind, scientifically? For some, it is an useful abstraction that generalizes over a set of similar phenomenon. For example, “memory” is a shorthand for whenever we are able to recall a previous experience, be it what color shirt you wore on Tuesday, how your lunch smelled, or how ecstatic you felt after passing your exam. Judging by the current state of things, I don’t know whether these abstractions are more useful or more hurtful for scientific progress, at least in neuroscience. Because of the vague, non-descriptiveness of “memory” as a metaphor, we’ve had to come up with more discrete versions, like visual memory, auditory memory, affective memory, working memory, short term memory, long term memory, episodic memory, procedural memory, and the list goes on. But then why not study the brain as a purely physical system coupled to the rest of your body? After all, it would have tremendous practical utility in clinical applications, like for treating those with neurological and psychiatric disorders. My speculation is that using words like these allows us to tie the science of cognition back to our daily experiences, which is ultimately what we’re interested in. Some people are truly fascinated by how a specific ion channel contributes to the dynamic of a nerve cell, to which I say: “good for you, we need more people like you.” But I would say most people interested in cognition - scientists and the general public - are those that are in it for the philosophical reason, that perhaps by characterizing it scientifically, it would give our experiences regularity and meaning, rhyme and reason for their existence. In fact, I would say that the current infatuation that society at large has with neuroscience is really a misplaced fascination in psychology. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, people care about things that are relevant for them, and neuroscience can contribute to that in two ways: understanding brain diseases, and understanding our daily mental experiences. Except, now I’m not so convinced that it can ever do the latter.